“You’re killing an innocent man,” uttered Daniel Lewis Lee.

He felt the drip from the IV in his arm as he asserted he was “on the other end of the country” at the time of the murders. He asked that after his death the 10 assembled mainstream-media witnesses investigate why his federal judge barred the DNA testing of a hair sample.

Then the executioner started the lethal injection, ending a bipartisan 17-year moratorium on the federal death penalty. Twenty minutes later Lee was dead.

Subsequently none of those mainstream-media witnesses publicly vetted Lee’s claims. (Instead some did describe how Lee’s execution affected them.)

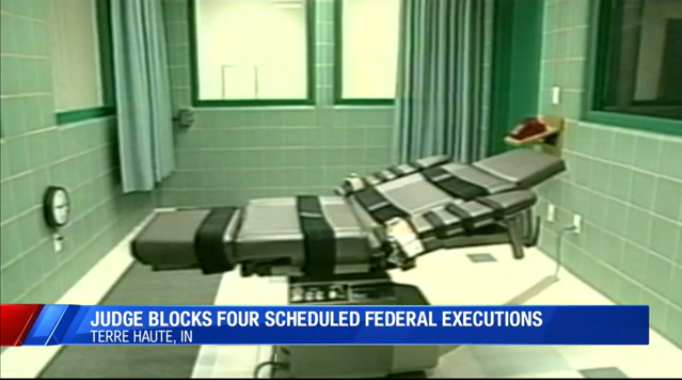

That was July 2020. Democratic presidential nominee Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. was still on the campaign trail, pledging to restore America’s soul. President Donald John Trump Sr. was perhaps at the peak of his administration’s war on “the China plague,” Covid-19. Lee was strapped to a gurney in Terre Haute, Indiana, aka home of the federal execution chamber (and pronounced terr-rah hoe-ght.) I was a stone’s throw away, locked down, serving 10 years for fighting to save kids from vicious abuses like these described in this Congressional testimony:

That lockdown lasted five days while the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) and former U.S. Attorney General William Barr put to death in rapid succession Daniel Lewis Lee, Wesley Ira Purkey, and Dustin Lee Honken.

Meanwhile Barr and the BOP had lost 100 other lives nationwide to Covid-19. To slow the spread, the BOP had months-long suspensions in place of all prison transfers and in-person visits, including attorney-client consultations.

But here in Indiana—where Trump smashed Biden by 19 points—executions are big business. Hundreds of staffers work at the federal correctional complex (FCC) that I and 3,000 other prisoners reluctantly call home. The sprawling, approximately 1145-acre federal compound is thus the sixth-largest employer in the city.

To administrators here executions equal media attention, politicking and career advancement. They gathered officials and witnesses from across the U.S. inside this complex, in close quarters, for each execution. Between Honken’s date with the needle and Biden’s inauguration six months later, they conducted 10 more lethal injections, for a grand total of 13.

Eric Williams was an executioner for five of them. Under penalty of perjury, he uniformly told federal courts the deaths were peaceful and painless, in order to counter legal claims that the execution drug pentobarbital causes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

But media witnesses and others provide different accounts. Dying prisoners, according to the Associated Press (AP), “rolled, shook and shuddered” their stomachs.

William Breeden was spiritual advisor to Corey Johnson during his January 14 lethal injection. As such, Breeden was inside the execution chamber with Johnson.

“Corey said his hands and mouth were burning,” Breeden filed the next day, under penalty of perjury.

Rick Winter, an attorney for the prison, filed a counterclaim swearing that neither he nor anyone in a government witness room heard Johnson’s statement. The AP, however, reports that before each lethal injection the prison disabled the audio feed from the execution chamber.

The AP and others also witnessed the September 22 execution of William Emmett LeCroy. His “stomach area heaved uncontrollably immediately after the pentobarbital injection,” the AP noted. “It lasted about one minute.”

According to Williams the executioner, however, “During the entirety of the execution, LeCroy did not appear to be in any sort of distress, discomfort, or pain.”

“A short time after he took a deep breath and snored,” Williams continued, “it appeared to me that LeCroy was in a deep, comfortable sleep.”

But Williams’s narrative fuels rather than settles the controversy.

“The sworn accounts by executioners, which government filings cited as evidence the lethal injections were going smoothly, raise questions about whether officials misled courts to ensure the executions scheduled from July to mid-January were done before death penalty opponent Joe Biden became president,” wrote the AP.

And shortly after Williams’s disputed court filings, the BOP promoted him to interim warden of its New York Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC)—one of its highest-paid positions. I know that facility well; I waged a hunger strike in solitary confinement there in the same special-housing unit where Jeffrey Epstein later died mysteriously.

The Biden White House press office if it will keep Eric Williams, a Barr holdover who might’ve perjured himself about prisoner deaths, in charge of the facility where records were falsified the night Jeffrey Epstein died. The White House press office did not respond.

Wardens tend to stay at MCC New York no more than three years, then retire. That’s often just long enough to maximize their pensions at taxpayer expense.

As a BOP employee, Williams’s pension is determined by his three consecutive years of highest earnings, not, as one may assume, by his actual contributions into the pension fund. Meanwhile Williams’s salary is adjusted for the “local pay area” of MCC’s address in Park Row, Manhattan. Thus, after a few years, Williams could become the next in a series of MCC’s wardens to retire outside Manhattan with a lifelong taxpayer-funded pension calculated for one of the world’s most expensive areas.

DOJ Inspector General Michael Horowitz has been responsible for investigating waste, fraud, and abuse in the BOP since his Senate confirmation in April 2012. Stephanie Logan, spokesperson for the DOJ OIG, was asked whether on Horowitz’s watch across the last three administrations, if the BOP’s senior leaders gamed the federal pension system, at taxpayer expense, to unjustly enrich favored administrators, including each recent warden of MCC New York and the nearby Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC) in Brooklyn. Logan declined to comment.

By some standards though, the boosts to Williams’s pay and pension are modest. After Warden Harley G. Lappin oversaw the 2001 lethal injection of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh here in Terre Haute, the George W. Bush administration promoted Lappin to head the entire BOP.

Today Brian Lammer is Lappin’s successor as warden of the medium-security section of FCC Terre Haute, which, confusing as it may be, is known officially as a federal correctional institution (thus the medium-security FCI is within the larger FCC). And during the 17-year pause in executions, the BOP moved death row from here to across the complex, behind the walls of the high-security U.S. penitentiary. I now write from inside the old death-row building, the one that housed McVeigh.

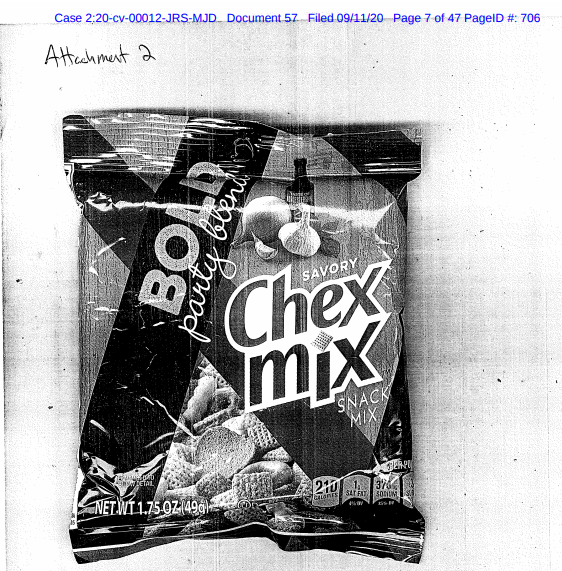

So although Lammer’s predecessors advanced considerably due to past executions, Lammer might’ve gotten ahead of himself in 2020 when executions resumed. Monday through Friday that week, and twice each day, Lammer served us prisoners Chex party mix. I filed the following in U.S. district court under the penalty of perjury:

U.S. court filing in Gottesfeld v. Lammer, 2:20-cv-00012-JRS-MJD, Dkt. 57, filed under penalty of perjury in the Southern District of Indiana (Sep. 2020, Public domain)

General Mills did not return a request for comment as to whether it sold BOLD party blend Chex Mix knowing that the BOP might celebrate lethal injections by serving it to locked-down prisoners.

The contradictory accounts of pentobarbital’s effects may raise Constitutional questions, according to Eric Berger, distinguished professor of Constitutional Law at Nebraska College of Law. Considered along with the back-to-back executions during a pandemic, the promotions, pensions, and party mix,

“It certainly suggests a callous attitude toward the condemned. Whether that amounts to a Constitutional question I think would depend on a lot of other facts that I don't have and that you might not have as to the details of the execution procedure they put together. In other words, they could be corrupt and totally callous, but still have designed an execution procedure that is reasonably safe and minimizes the risk of a painful death. But the fact that they're callous might suggest that they're the type of people who would not take care to minimize the odds of a painful death,” Berger surmised.

“The false pretenses under which the executions were carried out, the deliberate falsehoods that numerous Department of Justice and Bureau of Prisons officials told, the apparent enjoyment they received in inflicting emotional pain and mocking the suffering of the prisoners, suggests they weren’t indifferent to the prisoners’ needs, they were intentionally inflicting emotional distress” added executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, Robert Dunham. “That’s unprofessional, that should get them disciplined if not fired, and the Biden administration needs to take steps to make sure something like that never happens again.”

Southern District of Indiana Chief Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson, a 2010 Obama appointee, at least twice entered injunctions against federal executions due to the pandemic. Her first was July 10, three days before Daniel Lewis Lee’s date with the needle.

The family of the victims had sued Barr, claiming his rush during the pandemic left them with an “impossible choice.” Magnus-Stinson agreed, noting that the execution date would force one family member “to choose whether being present for the execution of a man responsible for the death of her daughter and granddaughter is worth defying her doctor's orders and risking her own life.”

“For us,” said relative Monica Veillette, “it is a matter of being there and saying, `This is not being done in our name; we do not want this.'"

The family had long requested a life sentence instead of death.

Unmoved, Barr pointed to improvised temperature checks and masking rules. He claimed the BOP could “carry out these execution[s] without being at risk.”

The next day the DOJ confirmed that an execution staffer had tested positive for coronavirus. Thus, some might’ve called the family’s lawsuit and Magnus-Stinson’s injunction prescient.

Ruling 48 hours later on a Sunday, however, three judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago stigmatized the litigation with the f-word of litigation: frivolous. Despite acknowledging divergent views among other federal appellate judges on the underlying nexus of federal and state laws, the Seventh Circuit panel held that surviving family members have no legal right to witness federal executions; therefore, their desires to attend are irrelevant. Pandemic or not, Barr and the BOP could simply carry on without them.

In originally bringing the suit, the family had been represented by lawyers from the Indiana ACLU. But attorneys are forbidden from making frivolous filings. So any future lawyer who makes a similar argument within the Seventh Circuit’s reach risks sanctions.

As for Chief Judge Magnus-Stinson, who found the family’s case not frivolous but injunction-worthy, the appellate judges chided her “reasoning,” saying it “seriously misreads” federal law.

Overall, the Seventh Circuit’s sharply worded opinion made clear that federal executions are not to be easily disturbed by lawyers and lower courts. Perhaps that was predictable in the federal justice system, where the executive branch both prosecutes the crimes and picks the judges, rewarding them with lifetime appointments.

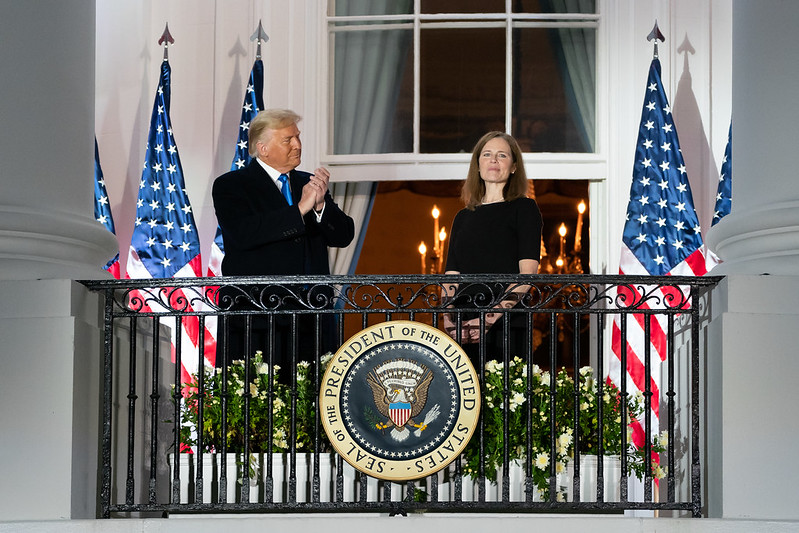

On the bench that day, allowing Lee’s landmark lethal injection to go forward absent the victims’ family, was the Seventh Circuit’s newest member: Amy Coney Barrett. And three months after Barrett voted in Barr’s favor, Trump favored Barrett to succeed Ruth Bader Ginsberg on the Supreme Court.

Then–Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett with President Trump three months after Barrett voted to proceed with the first federal execution in 17 years (Oct. 2020, Public Domain)

Magnus-Stinson didn’t enter another injunction against the BOP until six months later, after a joint session of the House and Senate certified the Electoral College vote, officially naming Biden president-elect. By then a third of the deaths at FCC Terre Haute weren’t from pentobarbital, but coronavirus and one case of blunt-force trauma.

Jose Nieves-Galarza, for example, was never sentenced to die. Yet in 2020 he was the first to leave FCC Terre Haute in a body bag, having never experienced Covid-19.

The 59-year-old was found in his cell May 5, months away from release on a seven-year bid (that’s a sentence to you folks) for being a felon in possession of a firearm. The cause of his death was homicide by blunt-force trauma and terminal exsanguination. In other words, he was beaten then he bled to death.

But that’s not what Warden Lammer told the public, or Nieves-Galarza’s family, or Senior U.S. District Judge Sylvia H. Rambo. Although the BOP’s press release expressly states coronavirus didn’t appear to be a factor in Nieves-Galarza’s death, it omits any mention of violence. To Judge Rambo, Lammer wrote that Nieves-Galarza had “passed away” from causes yet to be determined. And Nieves-Galarza’s niece, Diana Hernandez, said Lammer and his staff also didn’t tell her family about it.

“We were asking questions and they had no answers for us,” Hernandez told the AP. “I felt like I was getting blown off and getting the run-around.”

The FBI has been criminally investigating Nieves-Galarza’s death since around the time of the first federal lethal injection last July, but answers remain unforthcoming.

“The FBI should be no less responsive to the family than they are in any other investigation regardless of where the person was murdered,” retired corrections treatment specialist Jack Donson weighed in. “It's difficult for me to believe an investigation is ongoing a year later given the closed and controlled prison environment with cameras and snitches looking for a sentence reduction which is not uncommon for cooperation in a murder investigation. There must be more to the story.”

While Hernandez was burying her uncle the state of Indiana was coming to terms with spirits of its own.

Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett—elected in a county Biden later dominated by 28 points—ordered a Confederate monument disassembled and withdrawn from a city park. It had been moved there in 1928, when the KKK was active in local politics. The goal back then, according to the modern mayor’s office, was to “make the monument more visible to the public.” By June 2020, however, Hogsett said it “served as nothing more than a painful reminder of our state’s horrific embrace of the Ku Klux Klan a century ago.”

Five plaintiffs sued unsuccessfully to stop the monument’s removal. They pointed to its historical value and argued it was federal property. They claimed the city lacked the authority to destroy it.

“If the federal government”—i.e. The Trump administration— “would like to retrieve the monument, it can come and get it,” city and county attorney Donald Morgan told the IndyStar. “Some assembly will be required.”

A Confederate monument that was removed from Indianapolis’s Garfield Park on June 8, 2020. (2017, Public Domain.)

The monument was removed days after Biden clinched the Democratic nomination and one week before Barr announced the dates when federal executions would resume nearby. But the same week Daniel Lewis Lee, Wesley Ira Purkey, and Dustin Lee Honken met their fates in Terre Haute, the state of Indiana was still trying to exorcize its demons.

“When the Ku Klux Klan re-emerged in the 1920s more notorious and stronger than it had been after the Civil War, Indiana was its epicenter,” opened IndyStar’s John Tuohy the Sunday after those first federal executions. “At its peak 250,000 Hoosiers were card-carrying members. The ‘Grand Dragon’ was considered the most powerful person in the state, helping elect the governor and the mayor of Indianapolis.”

“It is well known that the Klan controlled politics,” affirmed former Indianapolis Urban League board member Joe Slash.

Clearly, though, not every recruit was a booster, according to Hamilton County, Indiana Historical Society researcher David Heighway. Some, he says, were intimidated into joining.

“In some instance[s], it was insurance to do business,” said Heighway, “while others could’ve been hardcore.”

“Certainly there was a good deal of intimidation—cross burnings being one blatant form, and of course [a] campaign aimed at Catholic and Jewish businesses,” said Brian Glover, age 67, who grew up Black in Noblesville, Indiana. “Klan speakers used churches, rallies and public forums to proclaim white supremacy and to verbally attack immigrants, Catholics, and Jews. The secrecy, and the use of hoods and robes could be intimidating.”

That secrecy intensified in 1925 when the grand dragon was imprisoned for killing a 20-year-old woman. But despite reports the Klan “came crashing down” that year, a quarter million members didn’t evaporate overnight. Incumbent politicians remained (and the aforementioned Confederate monument was yet to be placed prominently in a city park). In 1926 people continued signing membership cards, some of which were only made public 94 years later, in the same month federal executions resumed.

A lynch mob broke into an Indiana jail in 1930 and hanged two Black teens. A third was spared after someone vouched for him.

“The Klan was suspected of the killings, but it was never proven,” noted Tuohy.

Jim Crow laws remained on Indiana’s books until the Civil Rights movement. Glover recalls that his aunt and mother grew up with segregation in the 1930s and 40s.

“They felt it when they shopped, when they ate, when they went to the movie theater, in schools, in swimming pools,” Glover said. “Everything that was happening south of the Mason Dixon line was happening here, too.”

The present echoes the past. Before federal executions resumed in July 2020, thirty-five of the 62 federal death-row prisoners here in Terre Haute were minorities. Blacks were 12.6 percent of the U.S. population but 41.9 percent of the federally condemned.

More common than complexion, however, those facing Uncle SAM’s needle are universally poor. Perhaps only China executes billionaires.

So had Lezmond Charles Mitchell and Keith Dwayne Nelson knowingly downplayed the deadliness of a lucrative prescription opioid, contributing to nearly 1.5 times the domestic death toll of coronavirus, they might’ve paid the feds $8.3 billion to settle without jail time. Had they allowed shoddy equipment to spark repeated wildfires that killed 85, they might’ve bought their way out for $13.5 billion. And had they cut corners on an airliner that crashed twice, killing 346, they might’ve never been indicted.

But Mitchell and Nelson weren’t people who knew people. The feds didn’t let them declare bankruptcy and begin anew.

The DOJ strapped them to a gurney and injected each of them with five grams of pentobarbital. They died 46 hours apart, August 26 and 28, 2020.

Mitchell was the only Native American on federal death row. Navajo Nation opposed his execution for murders committed on its land.

“We can never lose sight of the big picture,” said Navajo Nation lawmaker Carl Slater before Mitchell’s lethal injection. “Every action creates precedent, especially when you’re a governing body. This is not just going to impact the Navajo Nation. It’s going to impact all of Indian Country.”

Over a dozen tribal leaders across the U.S. backed Navajo Nation’s request to Trump to commute Mitchell’s sentence to life without parole.

Others publicly disagreed, including family of the victims.

“An eye for an eye,” said the father of 9-year-old Tiffany Lee, whose throat was slit before she was bludgeoned with rocks. “He took my daughter away, and no remorse or anything like that. The Navajo Nation president, the [tribal] council, they don’t speak for me. I speak for myself and my daughter.”

Mitchell had “long maintained he wasn’t the aggressor in the killings,” reported the AP. “[Mitchell’s codefendant Johnny] Orsinger, now 35, had a criminal record but was a juvenile at the time and could not be sentenced to death. He is serving life in prison in Atlanta.”

Mitchell is the only Native American in modern history to be put to death by the federal government.

The day before Mitchell’s execution I tried to mail an open letter to Forbes journalist Walter Pavlo. Forbes and Pavlo unflatteringly but accurately covered the BOP’s bout with the coronavirus, so we’d corresponded.

The week leading up to Mitchell’s lethal injection was noteworthy. We’d been on total lockdown, unlike the week leading up to the earlier executions, presumably because the virus was spreading too fast to contain it otherwise. I wanted Pavlo to know that, and to advise him of events inside the federal death-row complex while coronavirus spread, and the BOP nonetheless proceeded with lethal injections.

Warden Lammer was again serving Chex party mix and I felt within my rights to mail Pavlo a letter for publication: The BOP had already battled federal prisoners in court over the right to publish articles and lost. The Supreme Court held in 1974 that prison authorities cannot withhold or censor prisoner mail they find simply unflattering or even inflammatory. And qualified immunity, a jailer's go-to get-out-of-court-free card, seemed used up.

But I was yet to learn the lengths to which FCC Terre Haute's attorneys would go to hit their execution dates. And federal courts are yet to call those lengths frivolous.

Wesley Ira Purkey's attorneys, for instance, claim FCC Terre Haute “stonewalled” them from gathering evidence to show he was mentally unfit. Daniel Lewis Lee's attorneys say prison authorities executed him "while multiple motions remained pending and without notice to counsel." The AP's question also remains unanswered: "whether officials misled courts to ensure the executions scheduled from July to mid-January were done before death penalty opponent Joe Biden became president." Those officials apparently include FCC Terre Haute attorney Rick Winter, who affirmed under penalty of perjury that he never heard Corey Johnson say his hands and mouth were burning.

There is a hint of political coordination too. After Lee's lethal injection, which the family of the victims publicly opposed, the 2020 Trump campaign sent a nationwide email saying Trump had "Ensured Total Justice for the Victims of an Evil Killer." The email also demanded Biden explain his opposition to the death penalty.

But the day after I handed my letter to prison authorities for mailing to Pavlo, I was nonetheless surprised that a lieutenant came to my cell to read me my rights for the prison-disciplinary process. Lammer had confiscated my letter. And the BOP's "counterterrorism unit" had charged me with trying to circumvent mail-monitoring protocols, supposedly by sending Pavlo a letter addressed directly to him and giving him my permission, in the public's interest, to publish it at Forbes.

“[FCC Terre Haute] Legal staff have been consulted throughout the review process," said the charging document.

John Childress is the acting U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Indiana, which includes Terre Haute. When Childress was asked if it is legally frivolous to charge a journalist with attempted circumvention of prison mail-monitoring because he sent a letter directly to another journalist for publication. Childress didn’t respond.

Under normal conditions prison discipline is hazardous. But at FCC Terre Haute coronavirus adds a new dimension.

Well into the pandemic BOP Disciplinary Hearing Officer (DHO) Jason Bradley contracted coronavirus. But that didn't stop him from entering FCC Terre Haute and sanctioning prisoners. And to say Bradley loosely complied with masking and social-distancing guidelines during that time would perhaps be generous.

The prisoners unlucky enough to interact with Bradley soon found they were punished beyond whatever sanctions he meted out officially. Even those who didn't contract Covid-19 were placed in weeks of inelegant quarantine in the form of solitary confinement.

Jason Bradley was asked to comment on his coronavirus diagnosis, his masking and social-distancing practices, and the quarantine of the prisoners and staff with whom he interacted. Bradley did not respond.

I had tried to write to Pavlo then too (and to others). The BOP's "counterterrorism unit" also blocked that correspondence, however I later filed a copy in court.

My earlier reporting on coronavirus at FCC Terre Haute was also blocked by the BOP's "counterterrorism unit," but made it onto federal-court record in Brown v. Federal Bureau of Prisons, 1:19-cv-02795 (RBW), dkt. 32 (D.D.C. July 22, 2020). (July 2020, Public Domain)

Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Representative Jerry Nadler (D-NY) respectively chair the Senate and House Judiciary Committees. When Emily Hampsten, communications director for Senator Durbin and John Doty, Nadler’s Washington director, were asked if limited federal counterterrorism funds are well spent by the Federal Bureau of Prisons counterterrorism unit when it blocks correspondence like the above from reaching credentialed American journalists at Forbes and other publications. Neither responded.

Six and a half hours after the lieutenant read me my rights, a deputy U.S. marshal read Lezmond Mitchell his death warrant and motioned to start the pentobarbital.

The next week the BOP made nationwide plans to resume in-person visits within a month's time. The move seemed rushed, as if in answer to criticism about gathering folks from disparate states inside a small building for executions while barring all other visits everywhere else.

"We believe this is a completely poor decision on behalf of the BOP and it will only fuel the fire… exposing staff and inmates to visitors from all over the nation," said Vic Rubinacci, first vice president of the AFGE Local 720, Terre Haute's prison-employee union.

When the story broke, the local Vigo County Health Department backed the BOP.

"We are very confident they [at the prison complex] have it under control and contained," said department spokesperson Roni Elder.

Eight days later prisoner Byron Dale Bird died of Covid-19. He was 65.

The day after that, prisoner Tim Hocutt, age 53, died within hours of testing positive.

More than 40 inmate cases were present in the complex 24 hours thereafter, September 15. Lethal injections went forward.

William Emmett LeCroy ate his last meal September 22.

Christopher Andre Vialva, the first Black prisoner to face the needle in 2020, was executed September 24. Less than a week later Barr scheduled a second, Orlando Cardia Hall.

"Five of the first six to die [by lethal injection] were white, which critics argued was a political calculation to avoid uproar," noted the AP. "The sixth was Navajo.”

"Questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system have been front and center since May, following the death of George Floyd after a white Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee on the handcuffed Black man's neck for several minutes.

"A recent report by the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center said Black people remain overrepresented on death row and that Black people who kill white people are far more likely to be sentenced to death than white people who kill Black people."

An all-white Texas jury agreed with federal prosecutors that Hall should die for his role in the kidnap, gang-rape, and murder of 16-year-old Lisa Rene. He was one of five perpetrators but the only one executed. Three, including Hall's brother, received lesser sentences in exchange for cooperation at trial. The other, Bruce Webster, had his death sentence vacated due to his intellectual disability.

Two days before Hall's execution on November 19, the Congressional Black Caucus sent Barr a letter. It stated that coronavirus "will make any scheduled execution a tinderbox for further outbreaks and exacerbate concerns over the possibility of miscarriage of justice."

Twenty-one days later cases at the complex numbered at least 326. Of the 1,316 high-security prisoners here, 128 had tested positive on December 8. In the medium-security section it was 198 of 887, or 45 percent.

Two days after these numbers were reported, the DOJ executed Brandon Anthony Micah Bernard, its third consecutive Black man.

"Bernard was not an architect of the robbery plan," reported the IndyStar, citing court documents. "He was 18 at the time."

Twenty-three hours later Alfred Bourgeois, also Black, went to his death on the federal gurney, professing innocence.

By December 22 the high-security section of the complex that houses death row reported 281 coronavirus cases, the most in the BOP. The New York Times reported that up to 14 of the 50 left on death row had tested positive, but that number might've been low.

"From talking to clients and other lawyers," said federal-capital-defense attorney Madeline S. Cohen, "I have heard that it is at least 28 guys."

According to Cohen the BOP was not providing accurate reporting on prisoners' health.

At least four at FCC Terre Haute had died of Covid-19. Lifer James Lee Wheeler had tested positive two days before Hall's execution. At age 78, he had multiple comorbidities indicating high risk. Lammer took eight days to send Wheeler to the hospital.

While doctors there fought to save Wheeler's life, Barr and the DOJ fought to expand their options to execute others. They moved to amend federal regulations to include not just lethal injection, but "any other manner [of death] prescribed by the law of the state in which the sentence was imposed."

Ngozi Ndulue is the senior director of research and special projects for the non-profit Death Penalty Information Center.

"Barr has really been aggressively pursuing executions," Ndulue told the IndyStar, "and part of that aggressive pursuit is this amendment."

The new regulation went into force December 24, allowing the DOJ to use nitrogen hypoxia, the electric chair, the poison-gas chamber, and firing squads.

But for James Wheeler death came by Covid-19 on December 7, three days before Bernard's lethal injection.

At some point that month Corey Johnson and Dustin John Higgs, who were scheduled to be the last prisoners executed before inauguration, also reportedly contracted coronavirus. But according to a court filing, BOP employee Andrew Sutton, their unit counselor, ended up leaving death row before they did.

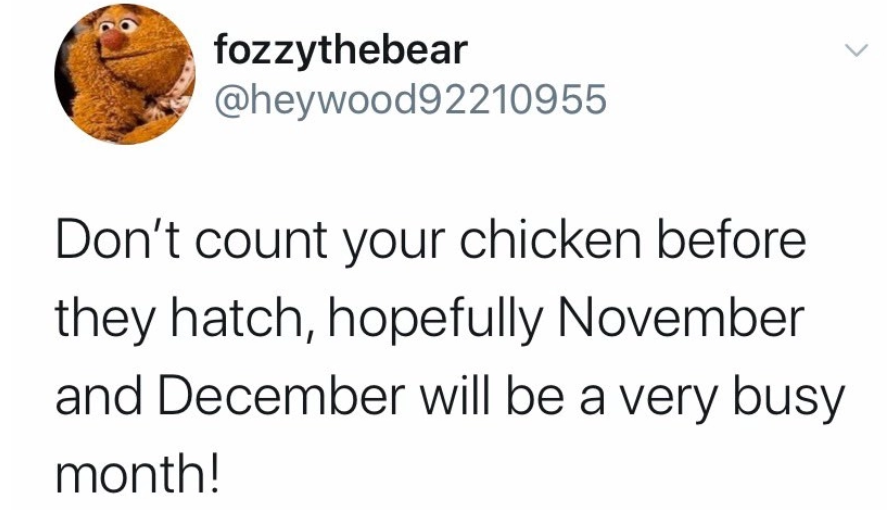

The defamation suit, filed on her own behalf by local attorney and anti-execution activist Ashley Kincaid Eve, links Sutton to an anonymous Twitter account making social media posts meant to defame a death-penalty opponent and cheer on the executions of the prisoners he was meant to advise (a BOP unit counselor is not a mental-health professional), including using information he learned in his professional capacity. While three executions were scheduled, fozzythebear tweeted “Don’t count your chicken [sic] before they hatch, hopefully November and December will be a [sic] very busy month!” for the Special Confinement Unit, or death row. The suit also claims that after Sutton’s posts, the BOP removed him from his job, although it’s unclear whether he’s been fired or reassigned.

Screenshots of tweet from fozzythebear mocking death row inmates.

Multiple local news outlets reported that Sutton declined to comment.

And Sutton is not the only death-row staffer to face allegations of inappropriate conduct.

Todd Royer is the unit manager of the special-confinement unit (SCU), otherwise known as death row. He is also the subject of complaints of voyeurism under The Prison Rape Elimination Act.

I first met Royer when I was sitting on the toilet in my cell defecating. He was the prison's duty officer that week and part of his job was to make rounds across the institution.

I declared that the following events are true and correct under penalty of perjury in federal court (and no indictment for perjury has been forthcoming): At the time my entire unit team was female and it's not uncommon for urinating or defecating male prisoners to be disciplined for "exposing" themselves to female staffers who happen to walk by. For the sake of everyone's comfort and dignity it is thus customary for prisoners to cover the windows in their cell doors while using the facilities, which I had done. Then an irate male voice hollered for me to uncover my door. The timing was awful but nonetheless I started to get up in order to comply when suddenly my cell door flew open and there was Royer, staring at me. Afterwards I found out I wasn't alone; that week he had busted in on several others in my unit while they were similarly indisposed. This issue was unique to Royer; no other staffer did this.

I tried to mail a complaint to the Inspector General's office but, as usual, the only answer I received was from Royer's coworkers here at the prison when they saw it. Then, the day after I filed a formal grievance, Warden Lammer threw me in solitary confinement. Shortly thereafter Lammer assigned Royer to manage my unit in addition to death row, as if to contain any other attempts to complain or file formal grievances.

Stephanie Logan, spokesperson for DOJ Inspector General Michael Horowitz, was asked if his office received PREA complaints against death-row unit manager Todd Royer, and, if so, why there have been no signs of an investigation. Logan declined to comment.

Royer himself did not respond to a request for comment.

And although the veracity of my declarations to federal courts remains unchallenged, the same cannot be said for the BOP.

"On December 4, 2020, defendant Warden [T.J.] Watson described the BOP's contact tracing procedures for a staff member who tested positive [for coronavirus] shortly before the July 2020 executions," noted Chief Judge Magnus-Stinson. "According to Warden Watson, '[t]he staff member's contacts were determined by the use of video as well as his personal recollection.' Warden Watson then declared under penalty of perjury that the 'BOP will continue to conduct the same contact tracing procedures if additional staff members test positive in the future.'” This declaration has proven to be wholly false.

"The most recent execution for which the [BOP] defendants have provided testing data was November 19. Within a week of that execution, six members of the execution team tested positive for COVID-19. The BOP conducted contact tracing for, at most, one of them.[...]

"Less than two weeks after the November 19 execution, confirmed active cases at the [high-security U.S. penitentiary] began rising. Within a month, the USP had added 400 new active cases— the most active cases among any BOP facility at the time.[...]"

(Chief Judge Magnus-Stinson's citations to the court record are omitted for readability; emphasis is Her Honor's own.)

Based upon her findings, Chief Judge Magnus-Stinson entered a second injunction against the BOP January 7, one week before the final scheduled executions of the Trump administration. But it wasn't everything the prisoner-plaintiffs wanted.

Instead of halting executions for the duration of the pandemic, Magnus-Stinson ruled the BOP could proceed so long as it enforced mask requirements, maintained contact logs for those involved with executions, required negative coronavirus test for 14 days after close contacts, and conducted contact tracing for any staffers who tested positive within those 14 days. Only time would tell the extent to which the BOP would comply.

The same day Magnus-Stinson entered the second injunction, Joseph Lee Fultz, age 52, entered Warden Lammer's custody. Four days later he tested positive for coronavirus. It would be a busy week.

Lisa Montgomery was the only woman awaiting federal execution. In late 2004 Montgomery contacted 23-year-old Bobbie Jo Stinnett. The two had met at a dog show and chatted online about Rat Terriers. Stinnett was a breeder with puppies to sell. She was also well into a pregnancy.

Under the pretense of buying a dog as a Christmas gift, Montgomery drove to visit Stinnett on December 16. Once inside the home, Montgomery strangled Stinnett and used a steak knife to cut out her baby. Montgomery was arrested shortly thereafter, while trying to pass off the child as her own.

Montgomery's attorneys argued she was not guilty due to mental incompetency and that she was unfit for execution. Her mother's excessive drinking while Montgomery was in the womb caused brain damage, according to court records.

"She was beaten, repeatedly raped by her stepfather and his friends, and sexually trafficked by her mother," noted The Topeka Capital Journal. "At 18, she married her stepbrother, who also beat and raped her. She had four children in less than four years before being sterilized. She lapsed increasingly into mental illness and repeatedly faked pregnancy."

Her execution had been postponed multiple times, including when her attorneys developed Covid-19 after making the four-flight round trip to visit her.

By early morning January 13, Montgomery's stays of execution ran out. Her appeal to Trump for clemency was unsuccessful. At 1:31 A.M. Montgomery was pronounced dead by lethal injection. She was the first woman the federal government executed since December 1953.

The next day also might've been historic.

"We are not aware of any other federal death penalty prisoner who has never had a single evidentiary hearing at which he could present his intellectual disability evidence," said lawyers Ronald J. Tabak and Donald P. Salzman when Barr scheduled the January 14 execution of their client Corey Johnson. "The government should not proceed with Mr. Johnson's execution in the absence of a thorough and fair opportunity for him to present this evidence."

But come January 14 the government nonetheless proceeded.

In its last week, the Trump administration was winding down and inauguration day was approaching. As law enforcement braced for an uneasy transition in the nation's capital, the BOP was on edge.

“In light of current events occurring around the country, and out of an abundance of caution," wrote the BOP, "the decision has been made to secure all institutions."

The lockdown took effect simultaneously at all 127 federal prisons at midnight January 16.

But would a national lockdown ahead of a historic inauguration stop the BOP from carrying out its thirteenth and final execution of the Trump administration? No.

Dustin John Higgs was pronounced dead an hour and twenty-three minutes later. He too died claiming to be innocent. But his was not the last death at FCC Terre Haute.

On January 25, two weeks after Joseph Lee Fultz tested positive for coronavirus, Warden Lammer classified Fultz as "recovered." But the 52-year-old would see neither the fourth week of the Biden administration nor an emergency room.

Staff found Fultz unresponsive in his cell February 7 and called emergency medical services (EMS), who pronounced him dead at the scene.

Fultz had been in Lammer's custody for exactly a month.

The BOP acknowledges Fultz had long-term, pre-existing conditions associated with high-risk Covid-19. But instead of taking him to the hospital, Lammer placed him in solitary confinement. Alongside 13 executions, he was the seventh federal prisoner at this complex to die of other causes and the sixth to die of Covid-19.

But will he be the last?

Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Representative Jerry Nadler (D-NY) respectively chair the Senate and House Judiciary Committees. Asked whether they'll convene hearings to probe the risks former Attorney General William Barr and the Federal Bureau of Prisons took while conducting executions during a pandemic and the executions' effects on the record-setting spread of coronavirus where they took place, neither John Doty, Nadler’s Washington director or Emily Hampsten, communications director for Senator Durbin, replied.

My date with the discipline officer came March 3, well into the Biden administration. Prison-disciplinary staffers here were still flouting social-distancing rules and defying Biden's new executive order requiring masking on federal property.

DHO D. Matthews brought us within inches of each other and lowered his mask around his chin, exposing his nose and mouth as he spoke while he conducted the hearing. As part of his official sanctions for my trying to write to Forbes during the second week of federal executions, I'll spend an additional 27 days in prison and it was three months until I next spoke to my wife.

The Biden White House was asked if its executive order on masking in federal buildings and lands applies to BOP disciplinary officers, including Mr. D. Matthews, who exposed his nose and mouth while violating social-distancing guidelines during disciplinary hearings in the FCI Terre Haute D-unit chow hall starting at 1:30 P.M. Wednesday, March 3, 2021. The Biden administration didn't respond.

The claims of innocence asserted in the last words of Daniel Lewis Lee, Alfred Bourgeois, and Dustin John Higgs, as well as by others who remain on federal death row, remain untested outside federal court.

The type of forensic hair analysis federal prosecutors used against Lee was discredited years ago by a study undertaken in part by The Innocence Project; in one case a hair that FBI-trained analysts determined to be a likely match for the accused instead belonged to a dog. In Lee's case the "likely match" remains unverified and unchallenged by DNA testing.

Lee's critics highlight he was a white supremacist at the time of the murders.

That's true. But is it proof of murder, or a convenient pre-emption? Does the DNA from the hair found at the scene match Lee? Does it implicate someone else? Does Lee's alibi hold? Did Barr execute an American for a crime he did not commit? And do Lee's beliefs render these questions inconsequential?

I digress.

Merrick Garland has been confirmed as U.S. attorney general, while holdover BOP Director Michael Carvajal remains in place, as do almost 50 federal prisoners awaiting execution.

Although candidate Biden decried the death penalty "now and in the future," his administration continues with each passing day to fund the federal death row at a cost of millions of federal tax dollars per year. If the transition in Washington has local consequences across America then Carvajal and Lammer—whose arrival here coincided with Barr's push to resume executions are yet to feel them.

The White House press office was asked whether Biden would keep in their positions overseeing hundreds of federal prisoners Warden T.J. Watson, who provided a "wholly false" declaration under penalty of perjury to Chief U.S. District Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson about contact tracing, and Warden Brian Lamer, who served party mix during lethal injections. The Biden administration did not respond.

And as I read the local Tribune Star, watch the local news, and peer out at Indiana through the slats in my KKK-era brick-and-steel window, never do I see demonstrators holding signs to defund death row. Unless that changes, Biden can apparently bide his time as the one person who in a pen stroke can put to death "death row" itself.

Marty Gottesfeld is an imprisoned journalist, called an Anonymous hacktivist, and senior systems engineer. More information is available on FreeMartyG.com and you can follow him @FreeMartyG on Facebook and Twitter.

Donate Now

Donate Now

Follow

Follow