TERRE HAUTE, INDIANA (FREEMARTYG)--U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr faces at least 1 significant obstacle in resurrecting the federal death penalty: The federal government hasn't executed anyone since 2003, until Tuesday.

Thus, Barr is trying to execute some prisoners who lingered on death row through the last part of George W. Bush's first term, all of his second term, the entire Obama administration, and the tenure of Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions.

Put another way, 17 years have passed along with an uninterrupted bipartisan line of 6 U.S. attorneys general who each dropped the ball: John Ashcroft, Alberto Gonzalez, Michael Mukasey, Eric Holder Jr., Loretta Lynch, and Jeff Sessions.

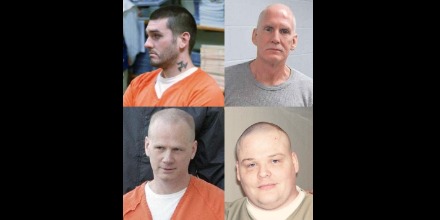

The condemned include Dustin Lee Honken, sentenced October 27, 2004, for fatally shooting a single mother and her daughters, aged 6 and 10, in Iowa. He faced the needle July 17, over 15.5 years later, until a court issued a stay.

Wesley Ira Purkey raped and murdered a 16-year-old girl and bludgeoned an 80-year-old woman to death in Missouri. He was sentenced January 23, 2004, and is set to die July 15, nearly 16.5 years later.

Daniel Lewis Lee was sentenced on May 13, 2002, for murdering an 8-year-old girl and her family in Arkansas. He was set to die July 15, nearly 16.5 years later, though the U.S. Court of Appeals for The Seventh Circuit recently stayed that date.

And Keith Dwayne Nelson was sentenced November 28, 2001, for kidnapping, raping, and strangling a 10-year-old Missouri girl. He is scheduled to die August 28, more than 18.5 years later.

"We owe it to the victims of these horrific crimes, and to the families left behind, to carry forward the sentence[s] imposed by our justice system," Attorney General Barr told the nation when he ordered the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to schedule the 4 lethal injections.

Legally speaking, however, Barr's predecessors greatly complicated this goal. One potential issue is the unsettled application of Due Process delay in capital cases

The Supreme Court alluded to Due Process delay without setting precedent in Betterman v. Montana. There, the defendant pleaded guilty to jumping bail and the government took 14 months to sentence him. Betterman asserted the wait violated his Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial.

The justices disagreed, finding the speedy-trial guarantee protects defendants who still enjoy the presumption of innocence, which was obviously inapplicable to Betterman after he pleaded guilty. (The Sixth Amendment explicitly protects "the accused," not those already found guilty.)

The court noted, however, that Betterman waived an argument under The Fifth Amendment that may have protected him: The delay violated his right to due process.

Unlike Sixth Amendment safeguards, the protections of The Fifth Amendment remain after a finding of guilt. Among them, of course, is The Due Process Clause: "No person shall be... deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law."

The Fifth Amendment thus explicitly protects condemned prisoners up through the moment they are "deprived of life."

The question remains, though, would the federal government deprive Nelson, Lee, Purkey, and Honken of due process by waiting 15-plus years to sentence them to death and lethally inject them?

And how would the courts decide?

After detouring because of Betterman, the likely answers are found by rejoining America's speedy-trial jurisprudence, specifically the case of Barker v. Wingo. Courts use the speedy-trial test from Barker to decide some due-process-delay cases too.

In Justice Sotomayor's concurring opinion in Betterman, she summarized:

Under the Barker test, courts consider four factors---the length of the delay, the reason for the delay, the defendant's assertion of his right, and prejudice to the defendant. None of the four factors is "either necessary or sufficient," and no one factor has a "talismanic qualit[y]."

Sotomayor also hinted that the Barker test is applicable to long delays in sentencing defendants, and that's about as close as the case law gets to the situation at hand, where the defendants were sentenced promptly but then waited over 15 years for execution. Moreover, it's an obvious advantage for the defendants to begin their arguments already aligned with one of the more liberal justices.

Factor 1: the length of the delays

This is known as the gateway factor. A finding of short delay almost always ends the analysis without the need even to examine the 3 other factors. The defendant must show that the length of the delay prejudiced him, i.e. adversely affected his ability to mount his defense.

The courts, however, maintain that a delay of over a year is "presumptively prejudicial." The defendants need prove nothing else to prevail on this factor, and, of course, the delays in these 4 death-penalty cases are much, much, longer than that.

So far, the balance heavily favors the defendants. But don't be surprised if the trial courts initially rule against them on this factor without examining the others. Lower courts hate Barker analyses and they frequently abort them as early as possible. Appellate courts, however, would likely hand the cases back to the trial courts for analyses of the remaining factors, thereby furthering the delays.

Factor 2: the reason for the delays

The most compelling Barker factor in these cases is the second. Courts attribute blame for delays either to a defendant or the government.

Of course, these defendants didn't delay their lethal injections for over 15 years. Instead, the government lacked the will to execute them.

So, the defendants could argue, they were put on hold until a president and attorney general came to power who had the backbone to carry out the courts' sentences. This distastefully and irrevocably injected politics into the judicial process and justice in America is supposed to be apolitical.

Under The Due Process Clause, the criminal-justice system must treat American citizens equally. The defendants could argue, for example, that due process is violated by holding some condemned prisoners on death row over 15 years---but not others---based solely upon the prevailing political situation at the time.

In any event, the delays cannot be attributed to the defendants and this factor also swings significantly in their favor.

Factor 3: the defendants' assertion of their right

The third factor asks when and how vigorously a defendant asserted his right against the unreasonable delay(s). In the speedy-trial context, this factor effectively bars a defendant from slow-walking then suddenly claiming he's been denied a speedy trial.

In the death-penalty context, however, a court might consider the absurdity of requiring a defendant to demand his own execution in order to color a claim of unreasonable delay. Yet the federal government is not without a counter-example: Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh dropped his federal appeals in order to expedite his execution. Had the government thereafter delayed McVeigh's lethal injection for 15 years, this factor would've swung heavily in his favor.

Still, weighed against the DOJ's inappropriate political considerations and 15-year delays---far longer than any, yet accrued in the speedy-trial context---courts could decide the aggregated balance of the first 3 factors favors the defendants. And for reasons delineated below, courts hold that when the first 3 factors favor the defendant, analysis of the fourth and final factor is often unnecessary.

Factor 4: prejudice to the defendants

In the speedy-trial context, prejudice to the defendant includes effects that reduce the reliability of a trial and the defendant's ability to mount an adequate defense: what courts call "oppressive pre-trial incarceration," the fading memories and availability of witnesses, and weakening of the defendants' community ties.

Courts also recognize that it's often impossible for defendants to prove these effects, so defendants can win by mustering a strong showing on just the first 3 factors.

In the death-penalty context, however, the defendants could argue their years under harsh conditions on death row render them now unable to fight the typical last-minute appeals in death-penalty cases. These appeals can only be filed when an execution date has been set, thus the government prevented the defendants from filing them earlier.

Even if successful, though, these appeals would not overturn the defendants' underlying convictions---which were procured in a timely fashion---but rather spare them the death penalty and get them moved from death row.

Now, of course, this argument is inapplicable to condemned killers who haven't experienced over 15 years of delay under harsh conditions. This is important because courts would not want to use these cases to set a wide-ranging precedent. So, by narrowly tailoring any relief to the extreme delays on death row, the courts would avoid affecting many cases while also sending a very important message to the Justice Department to keep politics away from the death penalty.

And that precedent is definitely worthwhile, the defendants could argue.

Marty Gottesfeld is an Obama-era political prisoner inside FCI Terre Haute. You can donate at FreeMartyG.com and follow @FreeMartyG Facebook and Twitter for updates.

Donate Now

Donate Now

Follow

Follow