Update: This article was updated on Thursday August 30th with news of the White House petition to call on Congress to protect free speech online, which is available here.

Not so long ago the mantra in America used to be, “I may disagree with what you have to say, but I will defend to my death your right to say it.”

Apparently not anymore.

Instead it seems that nowadays it's more common to hear that companies like Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Google, and their subsidiaries like YouTube are private companies and that as such they are free to dictate their Terms of Service (ToS) as they see fit, policing the speech on their platform according to their own standards of what they consider to be socially acceptable and handing out disciplinary consequences that few court judges would dare issue from the bench for fear of running afoul of the Constitution and humiliating themselves by overstepping their power and getting rebuked by higher courts.

Now, let's get some of the more concrete yet commonly misunderstood facts straight before a future article delving into the sociopolitical problems and the undemocratic oligopolistic nature of allowing a small number of tech giants to control so much of the worldwide political dialogue.

First, these are actually public companies – at least technically. Remember that Facebook (FB), Twitter (TWTR), Google (GOOGL) (which again controls YouTube), and Apple (AAPL) each have their shares publicly traded on the stock exchanges. That status of being publicly listed and publicly traded comes with broad implications as well as specific responsibilities both to shareholders and for the public. More on this point in the future.

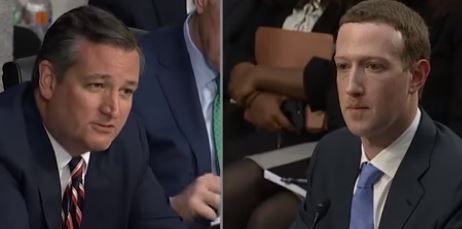

Second, by virtue of their nature as interactive computer services, these companies actually avoid legal liability for publishing what their users have to say. As you may recall, this topic came up in a limited fashion when Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) recently questioned Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg (?-Romulus) on Capitol Hill:

Now, when Senator Cruz was questioning Zuckerberg above, it was in regards to whether Facebook still qualifies for liability protection as an “interactive computer service” under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, given the widely-held and much-lamented belief that Facebook intentionally suppresses conservative content on its platform by hiding it from users. However, while the above is a well-known and noteworthy example, there are far broader implications to the status of these tech giants as public forums which hold far greater importance to the Internet as we know it.

You see, generally speaking, publishers are legally liable for what they print. For example, with exceptions for satire and the like, if a newspaper or magazine were to publish something untrue that damages someone's reputation, then the aggrieved party could win a lawsuit against that publication.

Now, it's been tenable to hold traditional media organizations accountable for what they publish because they can and usually do exercise pretty tight control over the content which they disseminate. However, social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and iTunes would face a nightmare scenario if they could be held liable as publishers for the content which their users post through their services. Just imagine if Facebook the company could be sued for any post made by any user on its platform.

Further, the sheer number of posts and audio and video recordings being constantly uploaded to these sites 24-7-365 makes it impossible for humans to review them all before they are distributed to other users.

This is where the “interactive computer service” concept comes in as this content is published without human review.

The notion behind Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields “interactive computer services” from legal liability for what their users post is that while Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and iTunes do publish and disseminate content in the traditional sense, they aren't like traditional publishers precisely because they don't control the content which their users share. The idea clearly behind Section 230 is that these websites are more like a public park where someone might get up on a soapbox with a megaphone and speak to whoever happens to be within earshot, and no one would hold the groundskeeper of a public park liable for what someone, unbeknownst to the groundskeeper, said to a crowd from atop a soapbox one afternoon with a megaphone.

Based on this concept, Facebook cannot be held liable for what its users post on its website, and indeed without such protection it's unlikely that any company would provide such a service for fear of losing lawsuit after lawsuit.

Further, as an important side note, this is not to say that you can't be sued for what you post to Facebook as a user. You most certainly can. It's Facebook as the interactive computer service which enjoys this liability protection and not you as the person on top of the soapbox with the megaphone who has both the choice and the control of what you say.

However, let's return to these “public forums.” Under any reasonable interpretation of Section 230 and the practical realities for which it was intended, these websites should truly have to make themselves neutral platforms in order to qualify for this protection from liability as publishers.

It is outside the spirit, if not the explicit letter of Section 230 for them to play traffic cop and control who gets up on the soapbox and who gathers round to hear them. When they do that, they are choosing not to be the interactive computer services contemplated by Section 230 at all but rather to behave like traditional publishers, complete with editors and an editorial process.

Tellingly, few if anyone in the legal world is saying that the New York Times, for example, qualifies for protection from liability for the content of the articles which it publishes on its website under Section 230, even though that website appears to meet the letter of the Section 230 definition of “an interactive computer service.” To further illustrate this point though, the New York Times clearly should enjoy Section 230 protection for the public comments left on its articles provided that its comment section remains a neutral public forum. And there is the crux of the issue – 2 distinct parts of the same interactive computer service – the New York Times website – where 1 – the content of the articles themselves – clearly should not and does not qualify for section 230 protection while another part – the comments section – is precisely the type of interactive computer service for which Section 230 was clearly intended, provided of course that human beings not wade into what is and what isn’t acceptable political speech there.

Any so-called “community standards” enforced by these interactive computer services should be entirely objective, akin to how the FCC enforces broadcast TV and radio stations to bleep over curse words. These kinds of objective safeguards and edits are in line with what Section 230 allows interactive computer services to do as well as with the standards to which private broadcasters are held on the public airwaves.

Further, “community standards” should not be used to target political ideologies or contested facts. If getting a story wrong is to be enough to silence publishers on social media, then shouldn’t the Associated Press have been suspended when it incorrectly reported that the Parkland shooter was a white supremacist? Shouldn’t CNN have been suspended when Jeffrey Toobin reported that Trump-appointee Acting U.S. Attorney Geoffrey Berman approved the raid on Michael Cohen’s law office? Or how about when the network incorrectly claimed that medical kidnappings were “unlikely” to occur in the United States where they in fact occur with startling regularity?

Shouldn’t the rules at least be applied uniformly to everybody?

But yet, as of now, that’s not what we’re seeing as these tech megaliths appear to be having their cake and eating it too. They effectively stand outside liability for the content published on their platforms while simultaneously exercising more and more control over who can get on top of the soapbox and who will be allowed to hear them. And many in the public are even applauding as these companies have their cake and eat it too, in a fashion that no private citizen could get away with.

As a result, dissenting voices are being preemptively silenced to great fanfare, not with gag orders or strategic lawsuits against public participation, which would be stifling and deleterious enough, but by self-appointed, extrajudicial (non-official) tribunals which appear not to be bound by the 1st Amendment. Our lawmakers should join Senator Cruz in demanding better, in demanding that these platforms either return to their vital role as neutral public forums or accept traditional legal liability as publishers who exercise control over the content which they distribute in manners similar to what we’re seeing these tech giants do today.

After this article first appeared at FreeMartyG a WhiteHouse.gov petition was started as a separate independent effort to call on Congress to take action protecting free speech online. Supporters may sign that petition here.

Marty is an Obama-era political prisoner. To donate to support him or follow him on social media through his unjust incarceration please go to FreeMartyG.com.

Donate Now

Donate Now

Follow

Follow