PLEASE NOTE: The author has made this series available at FreeMartyG.com under the latest Creative Commons by-attribution commercial-use-permitted share-alike no-derivatives license.

This is part 8. Click here to read Inside the Black Sites Where Obama, Clinton, and Holder Buried Their Secrets—Part 1 of the CMU Series or click here to read Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here—Part 7 of the CMU Series.

FBI Director Christopher A. Wray and his colleagues framed Robert Ethan Miller in the 1990s and he’s been in federal prison ever since, according to three witnesses who confess to following Wray’s instruction to lie under oath during Miller’s trial. Miller (not to be confused with Mueller) was the operational manager and part owner of the Gold Club on Atlanta’s busy Piedmont Road when Wray indicted him on charges of counterfeiting and conspiracy to kill a federal witness.

It’s the DOJ, however, that seems to be engaged in an ongoing conspiracy to cover for Wray, one that prevented the White House and the Senate from learning about Miller’s case in 2017, when the White House vetted Wray for the role of FBI Director and the Senate convened confirmation hearings.

Miller’s case appears reminiscent of a scandal that broke during Robert Mueller’s tenure as FBI Director. In 2007, Boston-based Senior Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, Nancy Gertner (since retired) ruled that multiple FBI directors and other top brass, indeed, “The entire FBI hierarchy,” going as far back as 1967, “was implicated” in the framing of four innocent men for a murder carried out by “Top Echelon” FBI informants. Judge Gertner also found that the FBI engaged in a decades-long cover-up, even after its chief trial witness, Joseph “The Animal” Barboza, had a crisis of conscience and tried to recant his false testimony.

Joseph “The Animal” Barboza had a crisis of conscience—unlike his FBI handlers—and tried to recant his false testimony after it was used to frame four innocent men. (Boston Police Department, 1965)

The new case started when Miller refused Wray’s demand to testify falsely against the Gambinos and the Gottis in 1997, says Miller. The DOJ has now held Miller nearly incommunicado for over a decade and interfered with his court filings due to his efforts to prove that he’s innocent; until today, his first chance to clear the air in a media interview about his experiences with Wray.

“I was told to say what they wanted to hear or I’d get 35 years,” Miller reports.

Miller and the three informants who helped convict him now stand firm against the DOJ and allege that Wray knowingly used bogus evidence and false sworn testimony to trick a federal judge and jury into sending Miller to federal prison to serve a three-and-a-half-decade sentence for made-up crimes. Miller has been locked up ever since—for what is now 22 years—while documents from his trial, including his indictment and sentencing transcript, have conspicuously gone missing from federal-court record.

Miller has spent much of that time in the DOJ’s communication management units (CMUs), where department personnel, particularly CMU administrator Katherine Siereveld, preemptively screen and block nearly all of his attempts to correspond with attorneys, family, friends, journalists, the courts, and the DOJ’s internal watchdog, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG). Miller reports that he only felt this scrutiny intensify after Wray was named to replace James Comey as FBI director.

The Senate confirmation of FBI Director Christopher Wray (picture) may have intensified the DOJ’s desire to keep Wray’s past in the past. (U.S. DOJ/ Public domain, 2017)

Records show that the DOJ spends tens of millions of tax dollars each year on its CMUs in order to keep a constant eye on about 80 of its roughly 175,000 federal prisoners Or put another way, Miller is among the 0.05% of the nationwide federal prison population whose communications most concern the upper echelons of the DOJ. Indeed, the DOJ seems less concerned by correspondence to and from record-setting Ponzi-schemer Bernie Madoff, because unlike Miller, the DOJ never put Madoff in a CMU.

And the DOJ’s apparent obsession with Miller’s communications seems to have little to do with organized crime—at least of the Italian-Mafia variety. Instead, Siereveld and the DOJ are blocking Miller from conferring with Wray’s other accusers, the men who now swear under penalty of perjury, with nothing apparent to gain for themselves, that Wray similarly threatened them with 30-year federal prison sentences if they refused to say what he wanted.

Thus, Miller is perhaps the latest stark reminder of an important lesson that seems to have been scorned repeatedly by FBI directors from J. Edgar Hoover to Robert Mueller, James Comey, and his replacement Christopher Wray: The ends of political advancement can’t always justify the means.

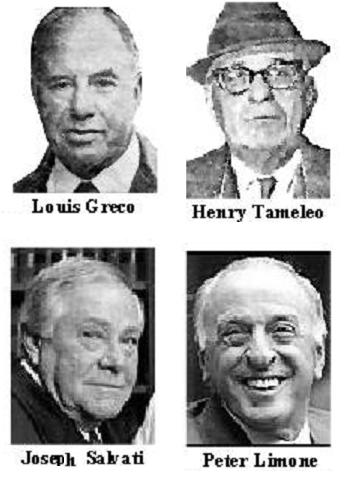

In the earlier example from the heyday of the “old” Boston FBI, decades before Wray allegedly was investigating the Gambinos and the Gottis, crooked agents who were supposed to be working to bring to justice La Cosa Nostra (LCN), (or Sicilian Mafia), instead knowingly used lying murderer/informant Joseph “The Animal” Barboza to frame four scapegoats, Enrico Tameleo, Louis Greco, Joseph Salvati, and Peter Limone, for the murder of a man named Edward Deegan, who in reality was killed by the FBI’s own “Top Echelon” informants. Salvati got life. Tameleo, Greco, and Limone were sentenced to die in the electric chair.

Four innocent men framed by the Boston FBI spent 30 years, or died, in prison before their convictions were overturned. (Courtesy of Hollywood Goodfella, date unknown)

That was 1968. In 1972, the Supreme Court struck down the sentencing procedure that was regularly used in death-penalty cases, and the three electrocutions were commuted to life imprisonment. (Four years later the Supreme Court approved a different sentencing procedure used today for death-penalty cases that requires a separate penalty phase, but death sentences that were already commuted, including the three in the Deegan case, didn’t change back.)

Regardless, Tameleo died in prison after 18 years. And Greco died behind bars a decade later—after he served 28 years—and after both men and their families first stared down the possibility they’d be executed for a crime they knew they didn’t commit, by absorbing 1,000+ volts of electricity while awake, strapped down, and fully conscious in the electric chair.

“I literally was not committing crimes,” Miller says now, referring to the 1990s when he was operator and minority owner of Atlanta’s Gold Club, which was well known as the biggest club in the city, as well as for its adult entertainment.

It was then, Miller says, that Wray, who at the time was an assistant U.S. attorney, demanded he testify against the Gambinos and the Gottis (who are of no known relation to reporter Martin Gottesfeld).

“They gave me a three-ring binder full of information and said, ‘Let us know what you know and everything will be good,’” Miller recounts, noting the agent’s poor grammar.

The procedure of giving potential witnesses information first, before asking what they know, is a commonly reported tactic to get unscrupulous informants to testify to whatever agents want from them.

“Secret Service Agent Donna James told me, ‘I know you’re innocent, Mr. Miller. I don’t want to see you go to prison for 35 years. But this is how the system works,’” Miller says.

A decade or so earlier, Miller’s father may have been a “made man” when he was murdered. Miller, whose family and friends call him Bobby, was 13 and had only recently started to get to know his dad at age 11.

Miller’s uncle was also murdered under similar circumstances when he was a boy.

Then, at age 18, Miller says he was attacked by two men, whom he shot in self-defense. He doesn’t believe the incident was related to the earlier murders. And state prosecutors seemed to credit Miller’s version of events. Charges were dropped as part of an agreement in which he enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

“I wanted to become a SEAL,” Miller says. “Two years in, though, they wouldn’t give me my rating and send me to the training program for Navy SEALs. So, I exercised an opt-out clause in my enlistment agreement. It gave me an honorable discharge if they hadn’t sent me to SEAL training by that point.”

Miller says he would rather have taken the SEAL training and stayed in the Navy, but after two years of getting the run-around, the chances of that seemed slim.

Miller was 19 when he left the Navy in 1989.

“I was below the drinking age,” he reflects.

The Gambino family may have wanted to “make me,” as Miller puts it.

“It’s not like the movies,” however, Miller says. “Not everybody wants to be made and wants to be a boss. I chose to get away from that life.”

Miller feels that in light of the murders of his father and his uncle, anyone who may have wanted him to follow in their footsteps would’ve understood his decision to leave the Northeast and get far away from that lifestyle. And he may have chosen well. Miller’s younger brother was later murdered, while he may have been becoming “a made man.”

Fresh out of the Navy, Miller says he was presented with other options. One of them may have been assuming operational management and minority ownership of the Gold Club in Atlanta, where Miller had acquaintances.

Rumeal Robinson, Miller’s friend from their time together at the noteworthy Rindge & Latin School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was drafted to the NBA in the first round by the young Atlanta Hawks franchise, after Robinson scored the winning free throws for the University of Michigan Wolverines in their 80-79 overtime victory against Seton Hall for the 1989 men’s NCAA Division I championship.

Rumeal Robinson throws the game-winning foul shot for Michigan in the 1989 NCAA—Division-I championship (YouTube screengrabs)

“Glen Rice was on that Wolverines team too,” pointed out Miller, who is an avid sports fan.

Miller soon found others drawing him to Atlanta as well, including Jennifer Ashford.

Asked if he was in love with Ashford, Miller quickly turned bashful. In a flash, 20 years of age seemed to disappear from his face as he gave in to a boyish smile and answered unequivocally, “Yes.”

There were no ifs, ands, or mays about Miller’s answer.

Soon, Miller and Ashford learned they were expecting a son.

Though Miller and Ashford later separated, Miller remained a dedicated father.

“I coached my son’s Pop-Warner football team, his baseball team, and his basketball team,” says Miller. “I was part of the PTA.”

That was before Miller met Wray, and before the CMUs.

“They’ve destroyed that whole relationship,” Miller now says regarding the long-term effect of the CMUs on him and his now—29-year-old son, who is older today than Miller was when Wray entered their lives.

Others also find it tough to maintain family ties in the CMUs. A federal appeals court in Washington, DC noted more than 3 years ago, in a case brought by the Manhattan-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), that CMU inmates like Miller, “may spend years denied contact with their loved ones and with diminished ability to communicate with them. The harms of these deprivations are heightened over time, as children grow older and relationships with the outside become more difficult to maintain.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals then quoted a lower federal court in Louisiana, reflecting on similar conditions, “With each passing day its effects are exponentially increased, just as surely as a single drop of water repeated endlessly will eventually bore through the hardest of stones.”

By the time the indictments started dropping and Miller’s name entered the news cycle in 1997, he had a new fiancé. He’d met Katherine Miller while he was out and about in Atlanta. Their common surname was just a coincidence and they quickly established that they weren’t relatives. This coincidence, however, would prove important after the authorities arrested Miller.

Katherine stood by Miller, who asserted that he was innocent while many in media labeled him “John Gotti, Jr.”

“She stood by me the whole time,” Miller says. “When I got to the CMU, they blocked her. She comes from a great family.”

Miller’s fiancé was adopted by James B. Miller, the source of her surname, and the founder and president of Fidelity National Bank, headquartered on Piedmont Road.

“I was engaged to marry into a banking family, why would I counterfeit $2,500?” asks Miller, referring to the small amount of cash that Wray initially alleged he counterfeited. “That makes no sense. Then, after I refused to lie, they hit me with the witness-tampering charge to raise the stakes.”

“They sent a lot of people into my cell block to inform on me,” Miller recalls. “One of them stole my mail from Katherine to see if there was anything he could use. Since Katherine and I have the same last name, he assumed we were married when we were not.”

The Cobb County Jail in Marietta, Georgia, where informants say the plot to frame Robert Miller got off the ground. (YouTube screengrab)

The man who grabbed Miller’s mail has since admitted that he helped Wray frame Miller on the witness-tampering charge.

“He said that he was willing to testify that I offered to pay him to kill my wife,” Miller says, “which is ridiculous because I didn’t have a wife. He just assumed that I did based on my mail from ‘Katherine Miller.’”

That narrative later changed, Miller says, to accuse him of plotting to kill Ashford, the mother of his son. Regardless, Miller’s supposed coconspirator is now adamant that in reality he and Miller never planned to harm anyone.

In fact, Robert Ethan Miller, Jr. at no time mentioned any desire or intention to kill [Ashford],” the informant declared under penalty of perjury on July 14th, 2005, some 12 years before Wray was named FBI director.

“When I told this to Mr. Wray, he told me that if I have told anyone else, I was going to jail for 30 years,” he declared again in 2018. “I was terrified by the threats made to me by Mr. Wray.”

“I don’t victimize people,” Miller says today. “I’ve never victimized people.”

The question now seems to be, can the same be said of FBI Director Wray?

One possible answer, taken from a sworn affidavit: “Mr. Wray’s office stole the lives of several families, while judges did all they could to cover up the fact that Mr. Miller was innocent, to keep the corruption out of public eyes.”

These and other documents from Miller’s case are available here.

At the end of the interview, Miller listens to the following introduction from Judge Gerner’s 287-page decision vindicating the four innocent men the FBI framed three decades before his similar experience.

Afterwards, Miller notes that what Gertner found is commonplace in today’s federal justice system.

“Why aren’t they correcting more people’s cases? He asks, “How do you still have my case after that?”

Despite the complexity of the record, this decision is far, far, longer than I would have wished. It has taken much more time to complete than I had predicted. But there was no other alternative. The conclusions that the plaintiffs have asked me to draw—that government agents suborned perjury, framed four innocent men, conspired to keep them in jail for three decades—are so shocking that I felt obliged to analyze this complex record with special care in order that the public, and especially the parties, could be fully confident of my conclusions.

I have concluded that the plaintiffs’ accusations that the United States government violated the law are proved. In the pages that follow, I will describe why in detail. This introduction summarizes some of those findings.

The plaintiffs were convicted of Deegan’s murder based on the perjured testimony of Joseph “The Animal” Barboza (“Barboza”). The FBI agents ‘handling” Barboza, Dennis Condon (“Condon”) and H. Paul Rico (“Rico”), and their superiors—all the way up to the FBI Director—knew that Barboza would perjure himself. They knew this because Barboza, a killer many times over, had told them so—directly and indirectly. Barboza’s testimony about the plaintiffs contradicted every shred of evidence in the FBI’s possession at the time— and the FBI had extraordinary information. Barboza’s testimony contradicted evidence from an illegal wiretap that had intercepted stunning plans for the Deegan murder before it had taken place, plans that never included the plaintiffs. It contradicted multiple reports from informants, including the very killers who were the FBI’s “Top Echelon” informants.

And even though the FBI knew Barboza’s story was false, they encouraged him to testify in the Deegan murder trial. They never bothered to tell the truth to the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office. Worse yet, they assured the District Attorney that Barboza’s story “checked out.”

The FBI knew Barboza’s testimony was perjured because they suborned that perjury. They met with Barboza long before the state authorities ever did. They coddled him, nurtured him, debriefed him, protected him, and rewarded him—no matter how much he lied. When Barboza told them he would not accuse the man they knew to be one of Deegan’s killers, his friend and FBI informant, Jimmy Flemmi, they urged Barboza to testify nonetheless. And when he announced that he would accuse four men who had never been linked to this murder, they were undaunted. The continued to press for his testimony. Indeed, they took steps to make certain that Barboza’s false story would withstand cross-examination, and even be corroborated by other witnesses.

In word and in deed, the FBI condoned Barboza’s lies. FBI agent Dennis Condon even told the Deegan jury that he was “always concerned with the purity of testimony on the part of” his witnesses, referring to Barboza, the perjurer. When Tameleo, Greco, and Limone were sentenced to death, Salvati to life imprisonment, the FBI did not stand silently; they congratulated the agents for a job well done.

Nor did the FBI’s misconduct stop after the plaintiffs were convicted. The plaintiffs appealed, filed motions for a new trial, one even took and passed a polygraph test on public television—over and over again protesting their innocence. They sought commutations, appeared before parole boards, seeking clemency from the governor, even appealing to the press. On each occasion, when asked about the plaintiffs, on each occasion when the FBI could have disclosed the truth—the perfidy of Barboza and their complicity in it—they did not. This was so even as more and more evidence surfaced casting more and more doubt on these convictions. In the 1970s, for example, Barboza tried to recant his testimony, not in all cases in which he had participated, but only as to the plaintiffs in this case—the very men the FBI knew to be innocent. In the 1980s, Agent Rico was found by a court to have suborned the perjury of another witness under similar circumstances. Yet, there was still no FBI investigation, no searching inquiry to see if an injustice had been done in this case.

Rather, while Salvati and Limone languished in jail for thirty-odd years, and Greco and Tameleo died in prison, Barboza and his FBI handlers flourished. The FBI agents were given raises and promotions precisely for their extraordinary role in procuring the Deegan convictions. Even when Barboza, the “poster boy” for the new federal witness protection program, committed yet another murder, three federal officials testified—now for the second time—on his behalf. FBI officials up the line allowed their employees to break laws, violate rules and ruin lives, interrupted only with the occasional burst of applause.

The FBI knew Barboza’s testimony was false, that the plaintiffs’ convictions had been procured by perjury, that critical exculpatory information had been withheld—but they did not flinch. After all, the killers they protected—Jimmy Flemmi, along with Barboza, and Jimmy’s brother, Stephen—were providing valued information in the “war” against the Italian Mafia, La Cosa Nostra (“LCN”). The pieties the FBI offered to justify their actions are the usual ones: The benefits outweighed the costs. Put otherwise, in terms that are more recently familiar, these four men were “collateral damage” in the LCN war. To the FBI, the plaintiffs’ lives, and those of their family, just did not matter. As Agent Rico put it in his testimony before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform, when asked if he had any remorse that four innocent men went to prison, he replied: “Would you like tears or something?”

Now is the time to say and say without equivocation: This “cost” to the liberty of four men, to our system of justice is not remotely acceptable. No man’s liberty is dispensable. No human being may be traded for another. Our system cherishes each individual. We have fought wars over this principle. We are still fighting those wars.

Sadly, when law enforcement perverts its mission, the criminal justice system does not easily self-correct. We understand that our system makes mistakes; we have appeals to address them, But this case goes beyond mistakes, beyond the unavoidable errors of a fallible system. This case is about intentional misconduct, subornation of perjury, conspiracy, the framing of innocent men. While judges are scrutinized—our decisions made in public and appealed—law enforcement decisions like these rarely see the light of day. The public necessarily relies on the integrity and professionalism of its officials.

It took nearly thirty years to uncover this injustice. It took the extraordinary efforts of [another] judge, a lawyer [Victor Garo], even a [news] reporter [Dan Rea of CBS4 Television Stations, who relentlessly pursued the case of Salvati’s innocence], to finally bring out the facts. Proof of innocence in this democracy should not depend upon efforts as gargantuan as these.

White House spokesperson Hogan Gidley did not immediately respond to a request for comment prior to publication as to whether the White House knew about the above information during Wray’s confirmation.

Senate Judiciary Chairman Lindsay Graham did not immediately respond] to a request for comment prior to publication as to whether the White House knew about the above information during Wray’s confirmation.

Francis Schaeffer Cox did not contribute to this part of the CMU Series due to an anticipated scheduling conflict.

Donate Now

Donate Now

Follow

Follow