Byline: By Martin Gottesfeld and Francis Schaeffer Cox

PLEASE NOTE: The authors have made this series available at FreeMartyG.com and FreeSchaeffer.com under the latest Creative Commons by-attribution commercial-use-permitted share-alike no-derivatives license.

This is part 2. Click here to read Inside the Black Sites Where Obama, Clinton, and Holder Buried Their Secrets—Part 1 of the CMU Series.

On June 19, 2008, Donald Reynolds was one of a very small number of African Americans in Tennessee to have "class-three federal stamps." The stamps allowed him to keep silenced fully automatic firearms without hassle from law enforcement, at least theoretically.

Reynolds had passed an extensive multi-federal-agency background check in order to qualify for the stamps. His name and fingerprints were then entered into a federal database that easily allows federal agents to browse lists of such weapons and their owners, almost as if they are window shopping.

Twenty-nine-year-old Reynolds kept his record spotless his entire life in order to maintain his eligibility to remain in that federal database.

"They knew I was one hundred percent legitimate," Reynolds points out now.

He adds that his entire family was background checked on a regular basis. His father held a security clearance and had not yet retired from Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Yet Reynolds's perfect record and his family's history of national service didn't seem to matter on that fateful pre-summer day. Federal agents, led by I.R.S. agent Brian Grove and Assistant U.S. Attorney Tracee Plowell, along with the local Knoxville, Tennessee, Police Department, still swarmed Reynolds's home and that of his parents nearby. They claimed they would find a large quantity of drugs.

Grove, Plowell, and their team did not find any controlled substances or piles of dirty cash on Reynolds that day though. And they never would.

But that didn't seem to matter then either. They still seized all of Reynolds's lawfully obtained and federally authorized fully automatic firearms and Reynolds has not seen them since, except in photographs.

Later, similar (if not the same) weapons were recovered from the bloodstained hands of violent drug-cartel members south of the U.S.-Mexico border, in the aftermath of the Justice Department's poorly thought out Operation Fast and Furious.

D.O.J.-planners named the operation after the popular street-racing movie franchise, and it was, perhaps, an even less-realistic concept.

Some ideas, Some ideas, perhaps, should stay in the. movies. (Screengrab from 2 Fast 2 Furious movie)

Some ideas, Some ideas, perhaps, should stay in the. movies. (Screengrab from 2 Fast 2 Furious movie)

The idea was that federal agents would watch and record, but not immediately intercede or “take down,” the sales of firearms, including high capacity fully automatic weapons like Reynolds's, to arms smugglers who were suspected of supplying violent Mexican-drug-cartel members. Then the authorities would trace the weapons across the border and through to their delivery on the other side.

Fast and Furious turned into a disaster instead, and a full-blown public-relations nightmare for the D.O.J. Innocent victims, like U.S. Border Patrol Agent Brian A. Terry and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Special Agent Jaime Zapata, were mowed down by cartel members using the weapons before they were recovered. Others, like ICE Special Agent Victor Avila, were seriously wounded.

American casualties of the D.O.J.'s Operation Fast and Furious include U.S. Border Patrol Agent Brian A. Terry (left), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Special Agent Jaime Zapata (center) and ICE Special Agent Victor Avila (right), who were each shot by drug-cartel members using weapons “watched” by the U.S. Department of Justice. (L to R: U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, public domain; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), public domain; Fox News screengrab)

American casualties of the D.O.J.'s Operation Fast and Furious include U.S. Border Patrol Agent Brian A. Terry (left), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Special Agent Jaime Zapata (center) and ICE Special Agent Victor Avila (right), who were each shot by drug-cartel members using weapons “watched” by the U.S. Department of Justice. (L to R: U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, public domain; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), public domain; Fox News screengrab)

The truth eventually came out, that the killers only obtained the firearms thanks to the Justice Department.

Even before then, though, the Obama-Holder DOJ seemed to consider it an imperative to keep Reynolds quiet. But that would not be a simple matter.

Reynolds, who still maintains that he did nothing wrong, steadfastly refused to stay quiet and work for the feds as an informant and distributor, or to back down in court and take a plea deal that would have branded him a confessed drug dealer for life. He says his bail was revoked under a contrived scenario when he turned down the final such offer.

Reynolds then had no choice but to prepare for trial behind bars.

These weapons were sold to arms merchants and ten used by Mexican drug cartels to slaughter innocent people, as the D.O.J. sat idly by as part of its failed Operation Fast and Furious. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. A.T.F., public domain)

These weapons were sold to arms merchants and ten used by Mexican drug cartels to slaughter innocent people, as the D.O.J. sat idly by as part of its failed Operation Fast and Furious. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. A.T.F., public domain)

Reynolds planned to rely on his family and his music industry connections to get the word out about what happened—and how he was being set up by the Justice Department as a minority fall guy.

In November 2007, Reynolds signed a distribution deal—not with the feds or a drug cartel—but with Universal Records. Vegas Style Entertainment and its leader, Vince Carol, helped broker the deal. Reynolds hoped that his cousin, Jermany Victor James, who used the stage name Dirtbag and performed with legends like Sean P. Diddy Combs, would get high-profile musicians involved.

Jermany Victor James (second from left) in his break-through music video, Violator, with D.J. Khaled (right), also featuring Mystikal and Busta Rhymes. (Screengrab from music video)

Jermany Victor James (second from left) in his break-through music video, Violator, with D.J. Khaled (right), also featuring Mystikal and Busta Rhymes. (Screengrab from music video)

Reynolds now believes the feds threatened his cousin and others, including Reynolds's own employees, to stop them from providing evidence and testifying in his defense. He says James could've shown he legitimately earned the income that Grove claimed was drug money, among other things, and his employees could have backed up his alibi.

Reynolds also says he went through no fewer than 10 defense attorneys, but none were willing to confront, head-on, the D.O.J. and the corruption permeating his case. Instead, he says, they each started out strong, but then mysteriously started pushing him to accept a plea deal that seemed more in their best interests than his, or the public’s.

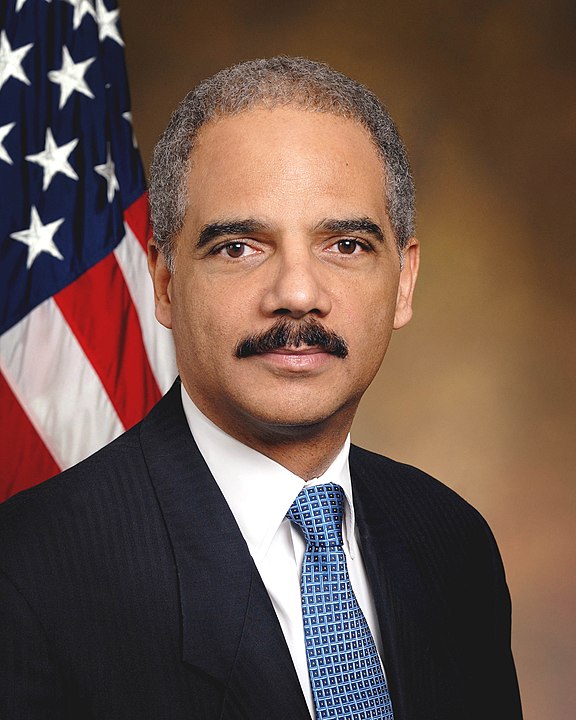

Adding to this mystique, Reynolds reports that Eric Holder personally attended some of his pretrial hearings.

Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder left office after Operation Fast and Furious and a number of other scandals, but before the end of the Obama administration. (U.S. Department of Justice, public domain)

Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder left office after Operation Fast and Furious and a number of other scandals, but before the end of the Obama administration. (U.S. Department of Justice, public domain)

The judge in Reynolds's case in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee was Thomas A. Varlan. Like any judge trying any case, Varlan was supposed to be neutral and detached. But the record reflects that Varlan represented the Knoxville Police Department in federal court before he became a judge. This was the same police department that participated in the raids on Reynolds and his family.

The trial transcripts from United States v. Donald Reynolds, perhaps unsurprisingly, exude a bias on the part of Judge Varlan, one that lay people perceive, in favor of the prosecution.

Reynolds says Varlan barred him from presenting evidence that contradicted prosecutors, and thereby prevented him from mounting an adequate defense to the jury. When prosecutors alleged that Reynolds used drug money for purchases, for example, Reynolds says Varlan blocked him from showing bank statements refuting those claims. And when the D.O.J. told the jury about the money-counting machines seized from Reynolds's home, he says Varlan prevented him from showing that he used them to handle in-person ticket sales at legitimate live events like concerts and parties.

Reynolds's trial transcripts also reveal a treasure trove months before the truth came out about Operation Fast and Furious, perhaps because at that point prosecutors had less to hide.

Across days of testimony in early 2010, for example, numerous undercover informants, including cartel smuggler and star witness Joshua Correa, detailed running assault rifles to Mexico, orchestrating hits, bringing thousands of kilos of cocaine, heroin, and other drugs across the border to Texas and more. Reynolds reports that he knew nothing about these activities before his trial, though he had done business with the legitimate auto-trading shop where Correa worked as a cover to mask illicit income.

Most of the government witnesses had signed cooperation agreements and were testifying against Reynolds in hope of receiving lighter sentences for themselves. They would have been scared for their lives, it seems from their testimony, to take the stand against cartel members. Testifying against Reynolds was seemingly a safer alternative for them.

Further, while Reynolds was standing trial from jail, Correa testified against him while out on bail, even though Correa was closely associated with the notoriously violent Zeta cartel and had personally helped order a hit on U.S. soil. When Reynolds's attorneys asked to see the order that U.S. District Court Judge Marcia A. Crone of the Eastern District of Texas issued allowing Correa to stay free pending sentencing despite his criminal history, the D.O.J. never provided it and Judge Varlan refused to order prosecutors to turn it over for use cross-examining Correa.

Correa also mentioned that his cartel had been looking for a "cop killer," i.e. a firearm capable of penetrating standard U.S. police-issued body armor, and that someone told him Reynolds could get such weapons. But not all the dots were visible to Reynolds until much later.

Only when Operation Fast and Furious made headlines, would Reynolds put it together; the testimony about running "cop killer" weapons down to Monterey, Mexico, about the Zetas, the plea deals for Correa and others, Correa's bail pending sentencing, Placido Benitez (a name Reynolds had never before heard), paid hits, and so-called "life debts."

In the meantime, he was fighting for his freedom in front of a judge he did not know had represented the police, against a drug-trafficking charge that was unsupported by the seizure of any drugs from him at any time, with lawyers who tried desperately to quit his case and coerce him into taking a plea he did not want.

Yes, according to the prosecution's own witnesses, all of Reynolds's firearms were legitimately purchased and properly permitted. No, most people who actually import hundreds of kilos of cocaine, as Reynolds was accused of doing, do not also jump through every state and federal hoop to register their weapons. That is like a bank robber running out mid-heist to top off a parking meter.

But, in the end, common sense is not so common—especially in federal court. The prosecution put on its show for weeks. Reynolds's defense attorneys rested his case after just one day.

"Guilty," came the verdict.

Life plus 75 years came the sentence from Judge Varlan—some 45 years longer than Joaquín El Chapo Guzmán Loera later received as an actual cartel kingpin. And Reynolds was a non-violent first-time offender. The D.O.J. charged him with importing 300 kilos of cocaine, while Correa, the trafficking mastermind who helped order a hit on American soil for the Zetas, was allowed to plea to trafficking 34 kilos instead of the 1,000-plus kilos he admitted to bringing across the border. Correa was then allowed to "earn" a further reduction to his sentence by testifying against Reynolds, a man whom, by all accounts, he had never met.

To the D.O.J. and many federal judges like Varian, this is justice.

When Reynolds heard about Operation Fast and Furious much later, it dawned on him. He would have been the ideal straw-man weapons purchaser for the D.O.J. He was young, well-connected, trusted in the hip-hop community, and he ran legitimate businesses that would've made an effective front. If any of his firearms were recovered, they would have traced back to him, giving his would-be handlers plausible deniability.

Wiser, but still undeterred, Reynolds kept trying to get his story out. And once he got to the F.C.I. Terre Haute communications management unit (C.M.U.), he started accumulating prison disciplinary charges due to those efforts, the First Amendment notwithstanding.

"It feels like there's really no such thing as the Constitution; like it's an illusion for the public to believe in, until it happens to them too—heaven forbid," Reynolds remarks now.

Reynolds also learned his actions as an inmate hidden in a C.M.U. can have dramatic consequences for his loved ones at home.

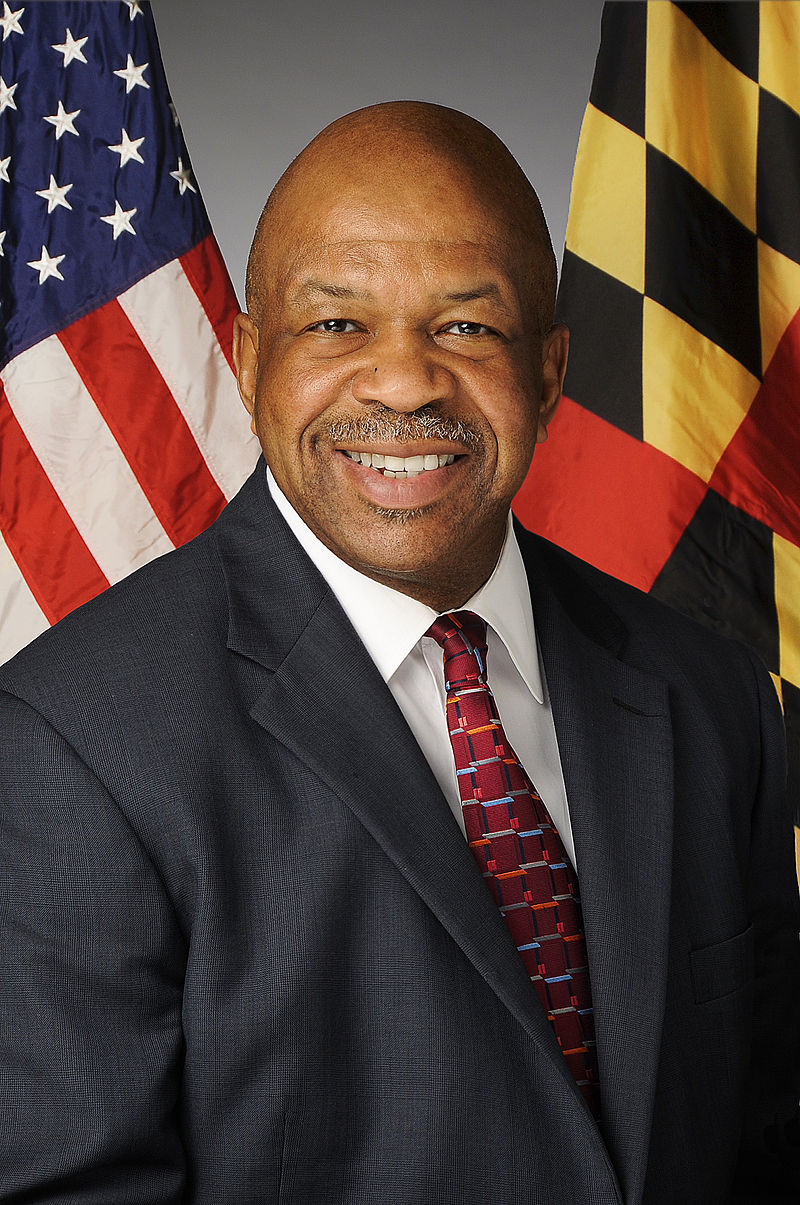

Reynolds tried to send a letter some months ago, for one possible example, to then–Chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Elijah Cummings (D-MD). Cummings's office previously helped curtail some potentially unlawful government activity against Reynolds when he reached out from another facility during his ill-fated appeal.

A little while after Reynolds tried to send this more recent message, however, a joint D.O.J. and local SWAT team went on a paramilitary-style raid of his mother's house mere minutes before Reynolds was scheduled for one of his two 15-minute-long live-monitored weekly telephone calls home.

When Reynolds greeted his mother on the phone that day, an assault rifle had just been pointed in her face from point-blank range.

This continued interference by the D.O.J. agents is only being carried out to impede on my rights and the facts that were not presented in my case. They are so determined not to have the public, nor the overseers in the House, such as Elijah Cummings, become aware of their misconduct—to avoid an investigation into years of government abuse of power used for their own personal benefit. It's not a coincidence that my placement in the C.M.U. is being used by these rogue government agents to identify and attack anyone who tries to aid in my liberty. If exposed, the results would show that my case and many others were knowingly created based on the lies of these agents in order to steal and subject Americans like me to losses of life, liberty, and property. It's no different from the time of King George III. What was the purpose of the Declaration of Independence? And the Bill of Rights?

–Donald Reynolds from the F.C.I. Terre Haute "black-site" communications management unit (C.M.U.)

Representative Cummings's office apparently never got the letter Reynolds recently sent, detailing how the D.O.J. tried to recruit him for Operation Fast and Furious and obtained his weapons, which would have traced back to Reynolds instead of the D.O.J. if not for the unexpected media revelations much later about the failed operation—and how he was railroaded by the I.R.S. and the Obama-Holder D.O.J. in order to cover their tracks.

As one might expect, correspondence commonly goes missing when sent from inside a C.M.U. to elected officials. Elsewhere in the federal prison system such letters qualify for special mail protections. But all such outgoing mail from a C.M.U. gets reviewed by the federal Bureau of Prisons before it is allowed to leave.

Letters sent by C.M.U. prisoners to Congressional representatives like former House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Chairman Elijah Cummings (D-MD) (pictured), often go missing. (Public domain)

Letters sent by C.M.U. prisoners to Congressional representatives like former House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Chairman Elijah Cummings (D-MD) (pictured), often go missing. (Public domain)

When Cummings passed away months after Reynolds’s quote above, mentioning him, Reynolds’s hope for help from Washington seemed to dim.

But Reynolds had just read Stonewalled by former CBS News journalist Sharyl Attkisson. Months after his trial, Attkisson broke the story on Fast and Furious at CBS. Her coverage won awards.

The Obama White House resisted bitterly, asserting executive privilege to keep documents secret. A top administration official had a brother who is a top CBS executive. And Attkisson’s computers and telephones started behaving strangely.

Multiple digital forensic teams confirmed Attkisson was the target of state-sponsored hackers. They found classified documents embedded deep in her computer, which could have been used to charge her criminally for unauthorized access.

But rather than back Attkisson, CBS seemed to back away from her. She eventually left the network.

Many questions remain about Operation Fast and Furious. And Reynolds’s case seems to fit like a missing puzzle piece.

After Stonewalled, Attkisson sued Eric Holder and other unnamed agents of the Obama administration. Her allegations of unlawful interference echo Reynolds’s, and she has now had her own experience going up against the D.O.J. in federal court. Her suit was dismissed without discovery, triggering a spirited dissent this May from U.S. Circuit Judge Andrew Wynn Jr.: “Attkisson never got a meaningful opportunity to pursue her claims because the government did everything in its power to run out the clock.”

Reynolds now hopes The Intercept, Michelle Malkin, David Knight, RT and others will interview Attkisson and ask her about being Stonewalled by the Obama Administration and not supported by fellow journalists.

“I hope they ask her what she thinks happened to my family,” Reynolds says.

And while their families may face suppression efforts on the outside, the inside of a C.M.U. can be an even more dangerous place for non-violent political prisoners like Reynolds.

Click here to read An ISIS-Inspired Murder and DOJ Cover-up in the CMU—Part 3 of the CMU Series.

Donate Now

Donate Now

Follow

Follow